Research Paper

The IR Research Paper is an annual print magazine introduced in 2024 to egage with writers and

activists

in collaborative study. Through in-depth conversations, curated artistically and socially relevant topics

that reflect intersectional perspectives

find display in an informative and accessible format.

In focus are

female artists and the human body as a surface for cultural discourses.

Issue #1 Preview

No. III

Shabah El Rih

Shabah El Rih, 2021

Whard Sleiman; Nader Bahsoun

Nowness Asia

By Mar Castañedo:

Mediums, as Patricia Darré describes them, are ghosts perceived in 2D - entities attached to walls, witnesses of history of certain places, embedded throughout constructions (2).

The opera singer Monà Hallab appears in a floating veil in the middle of

"Le Grand Théâtre des Mille et Une Nuits". The theatre in the centre of Beirut embodied an iconic of contemporary Middle Eastern culture until it was eventually abondoned after the civil war in 1975 (1).

We are, in fact, in the presence of a ghost. In this case, it is not confined to the walls of the space, but rather, it is in full flight, constantly moving. The manifestation must be linked to one of the metaphors that inhabit the name of this installation; the movement of the veil is as ethereal as the name:

"Shabah El Rih" or

"Second Wind".

The concept was created by Whard Sleiman with regard to its stage design, and Nader Bahsoun being responsible for the cinematography (1). Both decided to personify the vestiges of the past in an ghostly apparition.

Do we sometimes forget that we often refer to

"our past" as

"our ghosts"?

"Shabah El Rih"

represents the possibility of using the past during the present, putting forward the social consciousness that new generations possess and that the past is an identity that dwells within oneself and in history.

The installation is a re-signification that proposes the possibility of conserving and transforming through artistic sublimation. The symbolic rehabilitation of space means granting it this second breath that revitalizes it.

"Liebestod" (death of love) is the Wagnerian act that Hallab sings (3): every creation is an act of love, even if there’s a wink of misfortune and possible destruction of something important. The love for creation attempts to rescue everything. There‘s a sense that we will never be alone because violence accompanies us, even the ghosts, the latent reminiscence.

(1) Sihaam Naik, Shelley Jones. (2021) "Shabah El Rih – NOWNESS EXPERIMENTS," NOWNESS ASIA. Available at: https://www.nowness.asia/series/nowness-experiments/nowness-experiments-shabah-el-rih (Accessed: February 26, 2024).

(2) Dorothée Werner. (2024) “Patricia Darré: Les médiums sont des gens comme vous... et moi!“. ELLE France. Available at: https://www.elle.fr/Societe/Les-enquetes/Patricia-Darre-Les-mediums-sont-des-gens-comme-vous-et-moi-2465568 (Accessed: February 26, 2024).

(3) Richard Wagner. Munich Court Theater (1865) “Synopsis: Tristan und Isolde”. Available at: https://www.metopera.org/user-information/synopses-archive/tristan-und-isolde (Accessed: February 26, 2024)

No. II

“While You Are Sleeping” - Christina Bothwell

While You Are Sleeping, 2007

Christina Bothwell

By Fatima Njoya:

The essence of vulnerability is the fundamental inspiration in Bothwell's work, which engages a great deal with the body, its three-dimensionality and the transgression of any boundaries and possibilities of metamorphosis. All of these motifs come together again in her "While you are Sleeping" piece, created in 2007. Inspired by the artist's own vita, by the feeling of a lucid dreaming state of suspension in sleep during her pregnancy (5). Bothwell manifests this elusive state of sentiment in a material mix of colorless and white glass and fired Raku ceramics (2).

For Christina Bothwell ”(..) glass is an ideal vehicle to express the balance of life and spirit. In the one sense, glass is solid and heavy. But when glass is illuminated, it is transparent and fluid.” (4).

Not only the material shows a duality, but also the scene we are regarding - another body emerges from the sleeping woman lying on the floor, a body that also stands out due to the material used. The sleeping form, embodied by ceramics, while the spirit is mirrored by translucent glass (5).

According to Bothwell, it is one's own search for the 'true self', the 'fleeting sense of something more' (5). In the dream-like state whilst sleeping or the midst of its withdrawal, in which reality and fantasy become blurred, the search for meaning and longing of the sleeping woman is left to the eyes of the audience.

"While you are Sleeping" (2007) is one of Bothwell's own dearest works and is influenced by her greatest inspiration, which is dreaming (7).

"I have always been drawn to the ineffable-to the meaning that lies beneath the appearance of things. For me, glass is an ideal vehicle to express the balance of life and spirit. In my work, I like to explore the idea that we are more than just our physical bodies. I use glass to try and articulate what the non-physical is, that infinite quality of our spirit."

![]()

While You Are Sleeping,2007

Christina Bothwell

Bothwell’s work is about imagination, about immersing into art and musing about the “why” (6). Her intense preoccupation with the "Out of Body Experience" between birth, death and resurrection (3) is repeatedly reflected in her sculptures, that seem to step out of themselves.

(1) Bothwell, C. (2023) ‘BIO’, Christina Bothwell | Glass & Ceramic Sculptor, 30 December. Available at: https://christinabothwell.com/bio-2/ (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

(2) Bothwell, C. (2007) While You Are Sleeping [Colorless and white glass; cast; pit-fired raku ceramic.]. Available at: https://glasscollection.cmog.org/objects/38886/while-you-are-sleeping (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

(3) DailyArt (2023) While You Are Sleeping by Christina Bothwell via DailyArt mobile app. Available at: https://www.getdailyart.com/en/23050/christina-bothwell/while-you-are-sleeping (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

(4) Fellowship of PAFA.org (n.d.) Christina Bothwell, FPAFA. Available at: https://www.fellowshipgallery.org/copy-of-esai-alfredo-2 (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

(5) Lovelace, J. (2014) Divining Her Mediums, American Craft Council. Available at: https://www.craftcouncil.org/magazine/article/divining-her-mediums (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

(6) Riedel, M. (2012) Oral history interview with Christina Bothwell [The Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America]. The Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Available at: www.aaa.si.edu/askus.

(7) Salvator, F. (2019) Christina Bothwell - Coeval Magazine, COEVAL. Available at: https://www.coeval-magazine.com/coeval/christina-bothwell (Accessed: 30 December 2023).

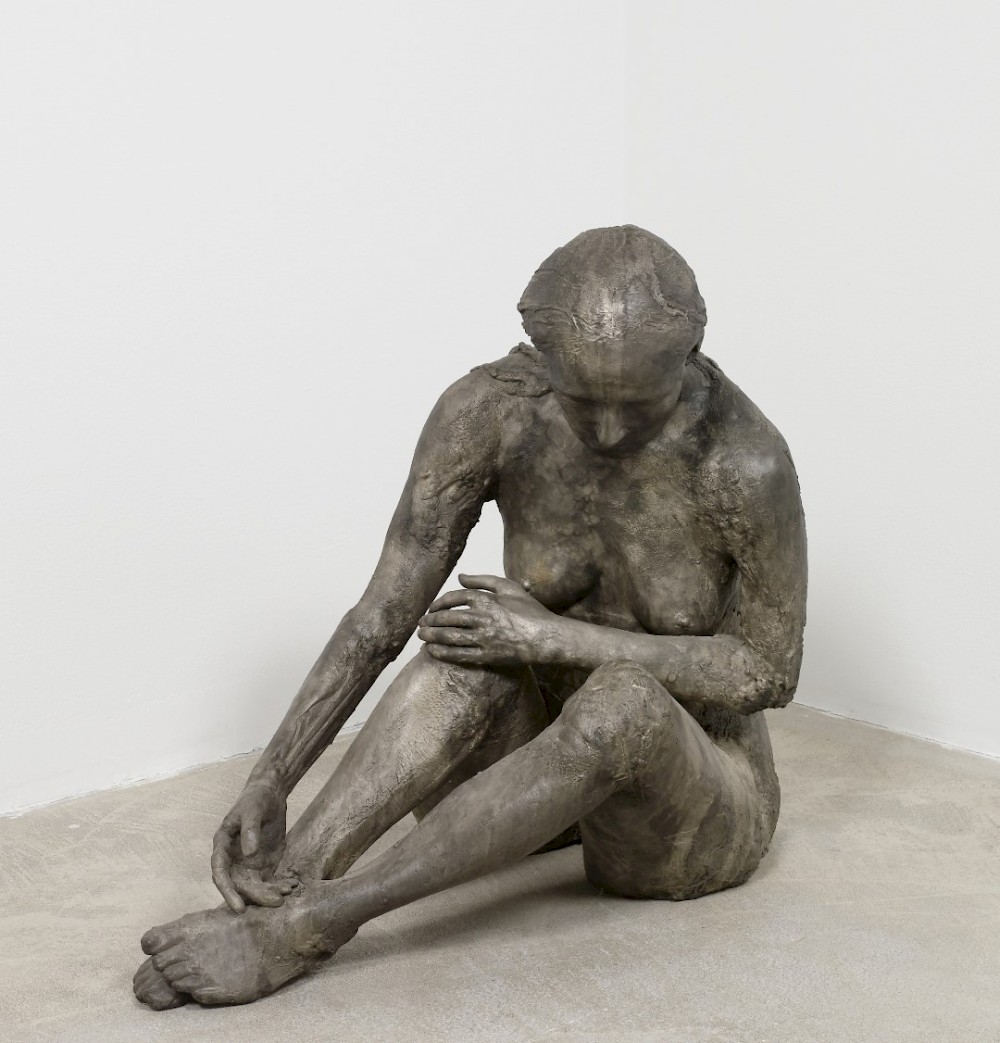

No. I

Kiki Smith

Woman in the corner, 2004

Kiki Smith

By Alice van Danisch:

A human-shaped tongue curving upwards, which seems to be having an animated conversation with the free-standing hand turned towards it: "Tongue and Hand" (1985) or the sinewy bronze woman crouching in the corner of the exhibition space: "Woman in the Corner" (2004). As we all know, art speaks for itself. Kiki Smith's artworks are surprising because they communicate with themselves within themselves. Her works defy conventional perception by dissecting the human body into its individual parts and placing it in a socio-politically accusatory context. The inner and outer corporeality and the engaging space in and around it have preoccupied the multimedia-working German-American artist since the beginning of her career at the end of the 1970s. Her radical depiction of body parts and fluids resonated strongly in America in the 1980s and 1990s, "where reproductive technology, feminist activism and the AIDS crisis placed the non-normative body at the center of a broader discourse on gender, origin and sexual identity” (1).

"I think I chose the body as a subject, not consciously, but because it is the one form that we all share. It's something that everybody has their own authentic experience with." (1990) (2).

In the constitution of commonality, which describes the sharing of our bodies as shaping us, there is the idea of a togetherness that is separated by the individual experience of each body. This "togetherness" also contains the "alongside each other", which the artist takes quite literally in "Untitled (Skins)" (1992) and aligns small square patches as "skin" surface to "skin" surface. The seemingly human is brought into shape, filed and displayed decoratively. Here, too, the "physicality" of the surfaces communicates in itself: sweeping elevations next to deep furrows, smoothness and roughness nestling against each other, like the contrasts of human inner life manifested as "skin" pieces made of metal.

![]()

Untitled (Skins), 1992

Kiki Smith

In Smiths' own perception of her work, the dichotomy and discrepancy between what is shown and what is perceived becomes clear once again. She describes her art as something holy that only ever reveals parts of itself to the outside world as well as to itself:

"Art is something that can stand for you, but it is not you and because of that it protects you, (so) that you can show a lot of yourself and still remain concealed. It can do both: the greatest possible exposure and the greatest possible distance. For me, it's like an amulet or a sacred necklace you can wear around your neck" (3).

(1) Okwui Enwezor in: Kiki Smith. Procession, exhibition catalog for Haus der Kunst Munich, Munich 2018, S. 7.

(2) "Hearing You With My Eyes", Kiki Smith, exhibition catalog for the exhibition "Kiki Smith. Hearing You With My Eyes" at the Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne (09/10/2020 – 10/01/2021), p. 16.

(3) Kiki Smith in an interview with Ariane Binder, 3Sat contribution to the artist's first major retrospective in Germany: "Procession", 2018, Haus der Kunst, Min 04:59 - 05:33.